Throughout this five-part series, we will cover the main components of the Science of Reading (SoR) and provide additional resources and research to guide your exploration and implementation of this important movement.

Say you’re given a passage of text to read. This particular paragraph describes half an inning of a made-up baseball game.

After you read the passage, you are asked to reenact the scene.

Which is more likely to aid your success?

A. Your ability to read

B. Your knowledge of baseball

C. It makes no difference

Would you be surprised to know the answer is actually B?

In part one of our series, “What is the Science of Reading anyway?,” we discussed the two main components of the Science of Reading: decoding (converting written words into speech) and language comprehension (understanding that speech). We also provided in-depth coverage of both learning and teaching how to decode the symbols of the English alphabet and strengthen the reading muscle.

LANGUAGE COMPREHENSION

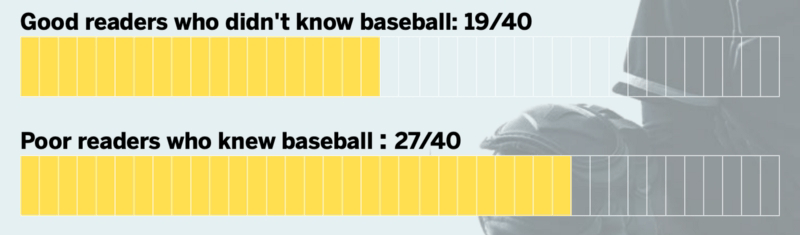

In 1988, two young researchers and 64 students took part in an experiment that has forever changed how we think about reading and comprehension. One by one, the students were handed the same story covering half an inning of a made-up baseball game and asked to reenact it.

To the researchers’ surprise, they found that reading ability had little impact on how well kids understood the story—but knowledge of baseball did. In fact, students who were weak readers did as well as strong readers if they had knowledge of baseball.

Teaching knowledge explicitly improves reading comprehension. As Willingham has said, “Reading tests are knowledge tests in disguise.”

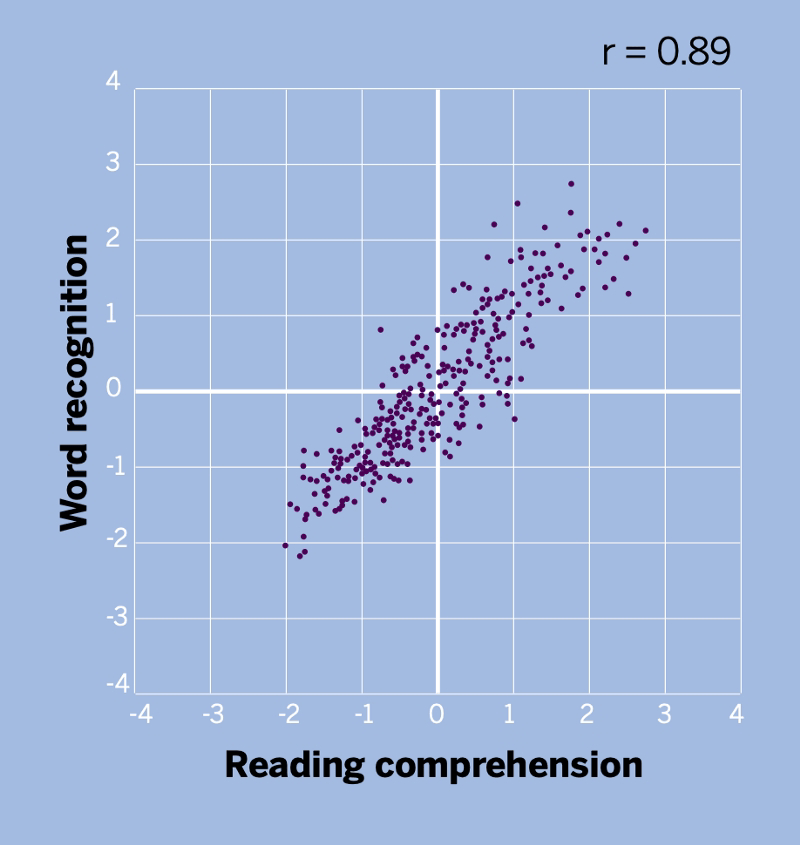

Researchers at the Haskins Lab at Yale tested this theory and found an extraordinarily high correlation between how well a 7-to-9-year-old child can recognize words and how well they comprehend text.

Common teaching mistake — Strategy instruction

So if reading comprehension is driven by a student’s vocabulary and knowledge, are widely taught strategies like finding the main idea equally critical?

Many strategies make intuitive sense: Stopping and re-reading when comprehension breaks down, for instance, is helpful for many children. But teaching the main idea strategy over and over is less helpful.

It is hard to find the main idea of a piece of writing if you don’t really understand any of the ideas in it. And even if you know a strategy — like re-reading when stuck — you also need to be well-versed in when to apply the strategy. You need to notice that you didn’t understand the text.

Often, strategy instruction neglects to offer students practice with identifying the situations in which they should use the strategy.

In the 1940s, a skills shift began to take place in education systems throughout the world. Its effects can be traced in the U.K., Sweden, Germany, and, most recently, France. This shift brought an emphasis on reading and math, squeezing out the broader knowledge taught in the sciences and social sciences. Some have linked the decline in standardized test scores—the SAT in the U.S. and the DEPP national exam in France—to this shift.

The National Survey of Science and Mathematics Education reported that today, classes in grades K–3 spend just 19 minutes per day on science and 16 minutes per day on social science.

To counter this loss of broader knowledge in our students, research suggests that we teach comprehension strategies in moderation and use the freed-up time to build knowledge (and vocabulary).

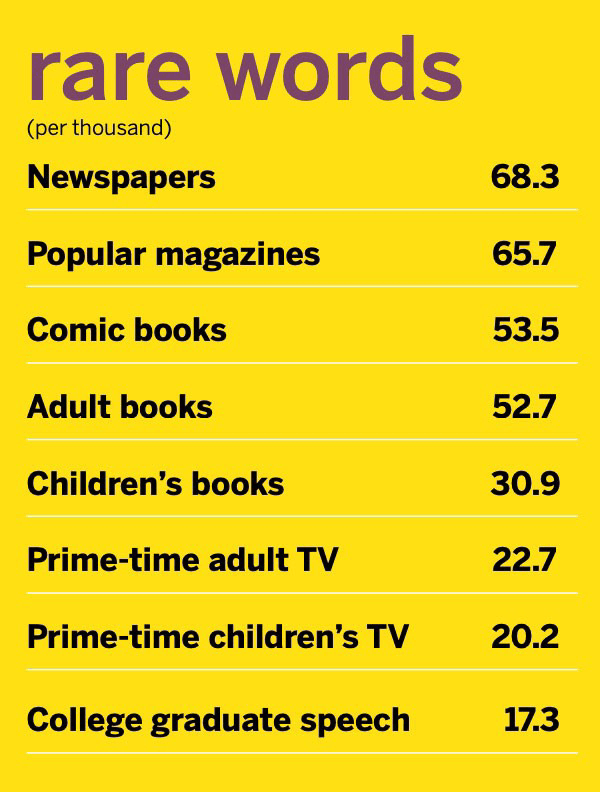

But simply exposing students to everyday speech doesn’t build a strong vocabulary. In a typical conversation, there are around 20 unusual words—such as dismayed or zeal—per 1000 words. Newspapers and books contain more than twice as many. Rich vocabulary, then, is gained not solely through speech, but through reading. Rich vocabulary, then, is gained not solely through speech, but through reading—especially when reading a variety of text types.

Mental models

Some readers with good word recognition, vocabulary, and knowledge are still weak comprehenders. Why might this be the case?

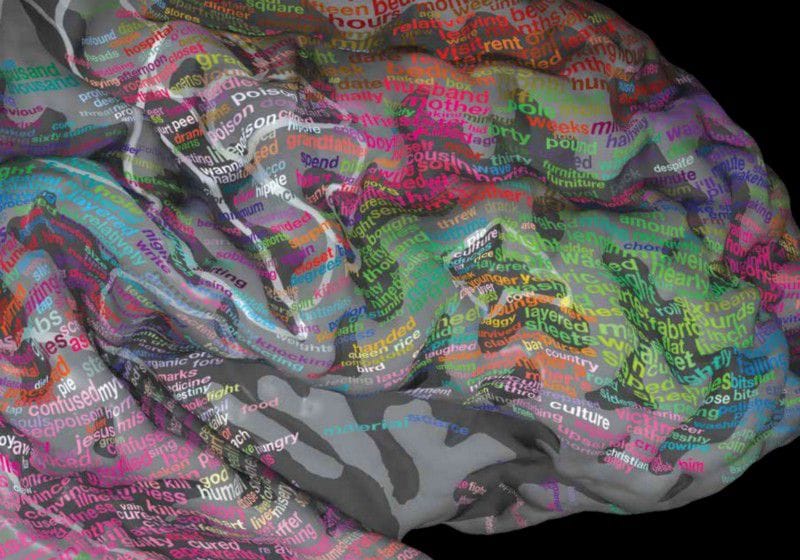

After students read a passage, they aren’t likely to recall the precise wording, but they will probably remember the ideas. Researchers use the term mental model to describe the structure you create in your mind to perform this feat of comprehension. Think of the process of building a mental model as a sort of micro-comprehension. Weak comprehenders build poor models. Hence, when asked prediction or mapping character development questions, they answer poorly.

There are four critical skills students need to improve their mental modeling:

- Decoding the usage of anaphoras (she, they, him). Some early readers can’t reliably figure out who the pronoun is referring to, especially in ambiguous text.

- Understanding the use of markers to signal ways that the text fits together — connectives, (like so, though, whenever) structure cues, and directions. Inexperienced readers may not know that but, though, yet, and however signal that something opposite follows.

- Writers make assumptions about what can be left unstated. For instance, when they read “Carla forgot her umbrella and got very wet today,” good readers will use their prior knowledge to conclude that it rained. Weaker readers who fail to make these gap-filling inferences wind up with gaps in their mental model.

- When something doesn’t make sense, you stop, re-read, and try to figure it out. Weaker readers just keep going—not because they’ve failed to figure it out, but because they’ve failed to notice that they don’t understand. They need explicit instruction in monitoring comprehension as they read.

Overview

Think of reading as a suitcase that you need two keys to open. The first key is word-level decoding, a skill that becomes automatic and fluent. The second key is language, vocabulary, and domain-specific knowledge. The more words you can decode, the more new words — and their meanings — you can learn. Similarly, the more knowledge you have on a topic, the more you can soak up on the same topic — and on related topics.

These two keys make up the Science of Reading. When schools focus heavily on one key or the other, the suitcase doesn’t open. So now the greater task of applying this knowledge in the classroom awaits us.

For more in-depth examples, brain scans, and information about the Science of Reading, download our free primer: