Many of us grew up doing a classroom activity called ŌĆ£reading comprehension,ŌĆØ in which we would read a short text about, letŌĆÖs say, sea turtles, then answer multiple-choice questions designed to demonstrate how much of that reading we comprehended. The next time, the reading might’ve been about the history of jazz.

Nothing against sea turtles or Dizzy Gillespie, but our approach to reading comprehension has evolvedŌĆöand thatŌĆÖs thanks to the Science of Reading.

LetŌĆÖs take a look at what we know now about how comprehension works and how to make it part of the best possible literacy instruction.

The role of comprehension in literacy instruction

Comprehension is one of the five foundational skills in reading and one of the two key components of the Simple View of Reading.

This framework lays out the two fundamental skills required for reading with comprehension:

- DecodingŌĆöthe ability to recognize written words

- Language comprehensionŌĆöunderstanding what words mean

In other words, reading proficiency is a product of word recognition and language comprehension.

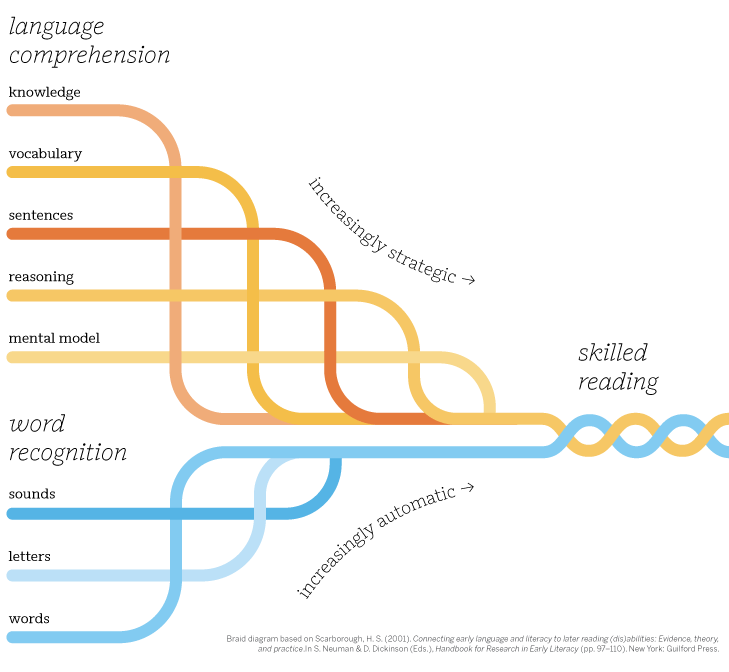

The Reading Rope layers complexity onto this view, providing a visual metaphor of reading as a complex skill combining decoding skills, language comprehension, background knowledge, vocabulary, and more.

In this context, comprehension refers to the ability to understand and make meaning from written text. It involves not only accurately decoding and recognizing words, but also grasping the deeper meaning, intent, and implications of the text.

Product vs. process: The missing link in comprehension

Historically, comprehension instruction focused on the products of comprehension, rather than on the process. Students could demonstrate that they understood what they just read about sea turtles, but how did students understand it? What were their brains actually doing at the time? Answering those questions can help us better support students.

To do that, letŌĆÖs look at the students who are not the best comprehendersŌĆöeven though they have solid word recognition, vocabulary, and background knowledge. WhatŌĆÖs missing?

After you read a piece of text, you’ll probably not recall its precise wording, but generally, youŌĆÖll remember the general idea. Doing so requires building a structure in your mind that researchers now call a ŌĆ£mental model.ŌĆØ The process of building a mental model is a sort of micro-comprehension.

Weak comprehenders build weak models. So when asked to analyze a character or make a prediction, their answers are not as strong as those of more advanced comprehenders.

We now know that students need four critical skills to improve their mental modeling/micro-comprehensionŌĆöand thus their overall comprehension.

- Interpreting the usage of anaphoras (like she, him, them).

- Understanding the use of markers to signal ways that the text fits togetherŌĆŖŌĆöŌĆŖconnectives (like so, though, whenever), structure cues, and directions.

- Supplying gap-filling inferences. (Writers often make assumptions about what can be left unstated, and weaker readers who fail to make these gap-filling inferences wind up with gaps in their mental models.)

- Monitoring comprehension as they read. (When something doesnŌĆÖt make sense, strong readers stop, re-read, and try to figure it out, while weaker readers just keep going, failing to notice that they donŌĆÖt understand.)

How background knowledge helps language comprehension

The Science of Reading demonstrates the importance of systematic and explicit phonics instruction.

But students do not have to learn phonics or decoding before knowledge comes into the equation.

ŌĆ£The background knowledge that children bring to a text is also a contributor to language comprehension,ŌĆØ says Sonia Cabell, associate professor at Florida State UniversityŌĆÖs School of Teacher Education, on Science of Reading: The Podcast. Background knowledge serves as the scaffolding upon which readers build connections between new information and what they already know. Students with average reading ability and some background knowledge of a topic will generally comprehend a text on that topic as well as stronger readers who lack that knowledge.

What we know about knowledge and comprehension should inform instruction. ŌĆ£I think most, if not every, theory of reading comprehension implicates knowledge,ŌĆØ says Cabell. ŌĆ£But that hasnŌĆÖt necessarily been translated into all of our instructional approaches.ŌĆØ

So, a central question is: How can we help build background knowledgeŌĆöand thus comprehension?

Broadly, we can work to use literacy curricula that intentionally and systematically builds knowledge as they go.

We can also be ŌĆ£intentional throughout our day in building childrenŌĆÖs knowledge,ŌĆØ says Cabell, offering the example of choosing books to read aloud. She suggests we ask not just ŌĆ£ŌĆśDo they have the background knowledge to understand something,ŌĆÖ but rather ŌĆśCan what IŌĆÖm reading aloud to them build background knowledge?ŌĆÖŌĆØ

Cabell also suggests being a little ambitious in your read-alouds: ŌĆ£Read aloud books a couple of grade levels above where [students are] reading right now, so that theyŌĆÖll be able to engage with rich academic language.ŌĆØ

Comprehension instruction in the classroom

So, what does this type of comprehension instruction look like? Let’s explore a few science-informed examples:

- Systematically build the knowledge that will become background knowledge. Use a curriculum grounded in topics that build on one another. ŌĆ£When related concepts and vocabulary show up in texts, students are more likely to retain information and acquire new knowledge,ŌĆØ even into the next grades, education and literacy experts Barbara Davidson and David Liben . “Knowledge sticks best when it has associated knowledge to attach to.ŌĆØ

- Present instruction that engages deeply with content. Research that studentsŌĆöand teachers, tooŌĆöactually find this content-priority approach more rewarding than, in Davidson and Liben’s words ŌĆ£jumping around from topic to topic in order to practice some comprehension strategy or skill.ŌĆØ

- Support students in acquiring vocabulary related to content.┬Ā Presenting key words and concepts prior to reading equips students to comprehend the text more deeply. Spending more time on each topic helps students learn more topic-related words and more general academic vocabulary theyŌĆÖll encounter in other texts.

- Use comprehension strategies in service of the content. While building knowledge systematically, teachers can use proven strategiesŌĆösuch as ŌĆ£chunkingŌĆØ and creating graphic organizersŌĆöto develop students’ skills for understanding other texts.

- Use discussions and writing to help students learn content. Invite students to share their interpretations, supporting them in articulating their thoughts and connecting with peers’ perspectives.

- Help students forge connections. Help students draw connections among lessons and unitsŌĆöand to their own experiencesŌĆöas they grow their knowledge together.

Comprehension goes beyond reading the words on a page. It involves actively engaging with the text, connecting ideas, drawing inferences, and relating the content to one’s own knowledge and experiences. By making sure students have the skills and knowledge they need to comprehend a text, we can help them comprehend the world.