Hear from science educator Valeria Rodriguez on our Science Connections podcast

In this episode of Science Connections: The Podcast, host Eric Cross sits down with , a Miami-based science educator, instructional technologist, and illustrator.

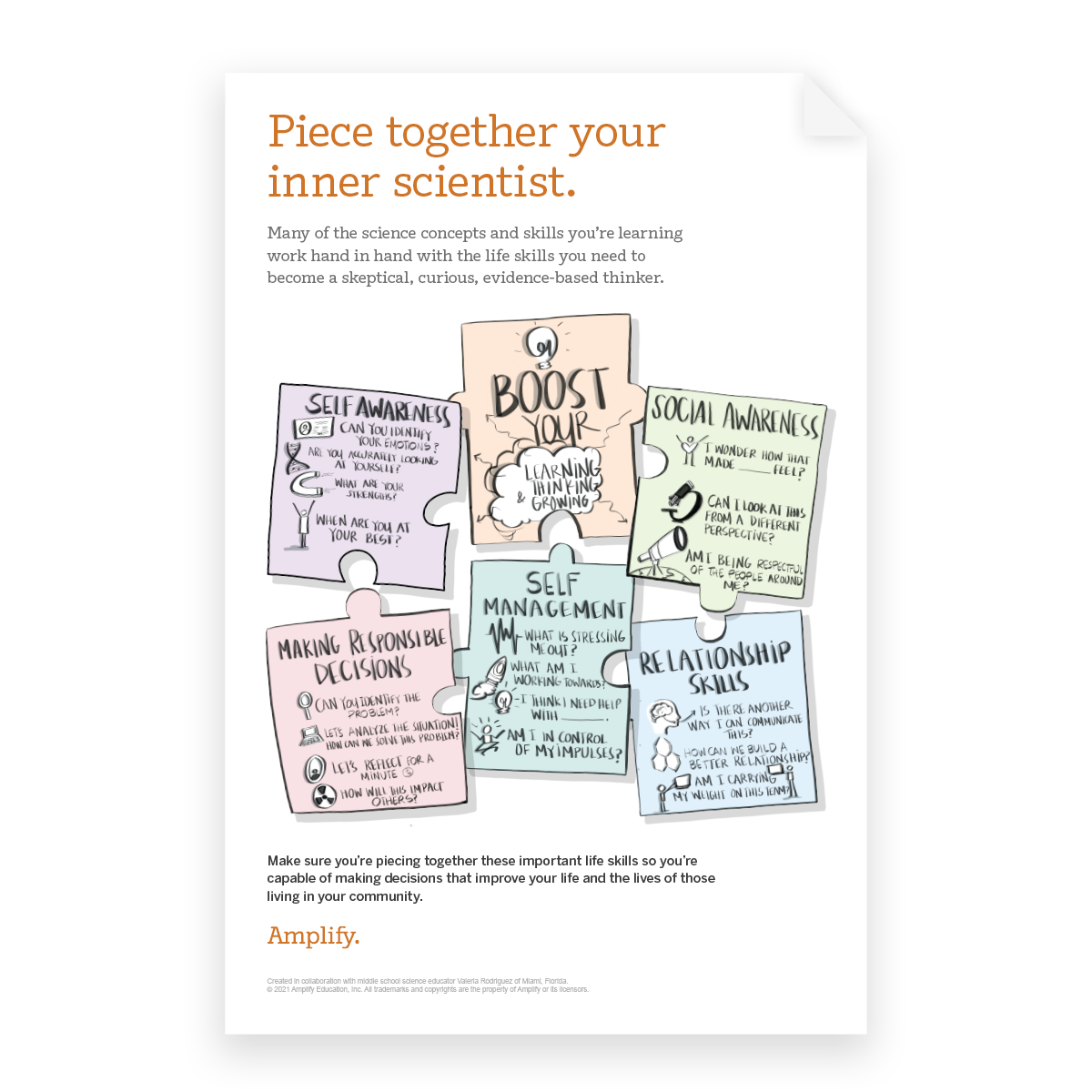

During the episode, Rodriguez describes how she uses real-world projects to make lessons more meaningful, and why teaching students to sketchnoteŌĆöa way of creating visual summaries of ideasŌĆöhelps them take risks they can learn from and increases their conceptual understanding in science.╠²

Read on for a peek at the episode, where youŌĆÖll learn more about the role of creativity in science and the importance of risk-taking in the classroom.╠²

Risk aversion among students today

Valeria is a science educator, instructional technologist, and illustrator (not to mention former college athlete and Peace Corps member). She also combines her science and art expertise to work as a graphic facilitator, which is her role on a STEAM team teaching third through fifth graders in Miami, FL.╠²

One thing Valeria has noticed in her classrooms is that her students often seem wary of taking risks and getting things wrong. How does she try to challenge and change this? Art.╠²

Valeria works with her students to use drawing as a form of note-taking. In the process, she says, ŌĆ£I mess up all the time. I scratch things out because my students in general are risk-averse. They donŌĆÖt want to make mistakes. And drawing is one of those things that taught me that itŌĆÖs okay to make mistakes.ŌĆØ┬Ā

Eric Cross says he sees the same risk aversion with his 7th graders. ŌĆ£When I ask them to give me a hypothesis about a phenomenon that IŌĆÖm going to teach, I say, ŌĆśItŌĆÖs okay to be wrongŌĆÖŌĆöbut I see them drift to the Chromebook and want to Google it.ŌĆØ

Creativity in science versus ŌĆ£getting it rightŌĆØ┬Ā

Sometimes risks lead to mistakes. But mistakes are not dead ends, these educators say. Mistakes are opportunities. They present opportunities not only for academic learning, but also for personal growth.╠²┬Ā

Of course, taking a risk may still deliver an expected or intended result. But even when it doesnŌĆÖt, that result can be valuable.╠²

Eric describes an activity where his students walk around the school campus swabbing various items to see what would grow in Petri dishes. ŌĆ£Some things grew and some things didnŌĆÖt.╠² Some of the experiments didnŌĆÖt yield the cool results,ŌĆØ he says.╠²

But that is exactly what gave the class the chance to speculate and learn about what factorsŌĆötemperature, a pathogen, the swabbing techniqueŌĆömight have prevented growth.╠²

Risk-taking also supports studentsŌĆÖ personal growth, often in ways that prepare them to learn even more.╠²

For one thing, taking risks helps students practice tolerating uncertainty.╠²

ŌĆ£Sometimes my kids are frustrated because I donŌĆÖt have yes or no answers,ŌĆØ says Valeria, citing the example of an activity with a weather balloon. ŌĆ£We donŌĆÖt know how high itŌĆÖs gonna go. Is the GPS tracker gonna work? We donŌĆÖt know, but we have to do all the steps and find out. I have to say, ŌĆśItŌĆÖs okay to be frustrated.ŌĆÖŌĆØ┬Ā

Taking risks can also lead to results that are less measurable, but equally valuable. When she does art and sketchnoting with her students, ŌĆ£Some people will say they ŌĆśmessed upŌĆÖ the drawing,ŌĆØ Valeria says. ŌĆ£But you know what? They gave it character.ŌĆØ

How teachers can model risk-taking

ŌĆ£Part of our job is also taking risks,ŌĆØ says Valeria, describing the time her class wound up having to do a tethered weather balloon launch because they couldnŌĆÖt get approval in time to launch the balloon in their location near an airport.╠²┬Ā

ŌĆ£A parent said, ŌĆśOh, youŌĆÖre not releasing the balloon,ŌĆÖŌĆØ she recalls. ŌĆ£I was like, ŌĆśWell, this is a lot of work, too, and I went back to my class and I was like, ŌĆ£You know what? I took a risk to do this project. I could have played it safe with a handout of a weather balloon,ŌĆØ she laughs, ŌĆ£or, you know, a YouTube video. But we are continuing to push.ŌĆØ┬Ā

She adds: ŌĆ£I want to thank the teachers who keep trying to do the hard things that arenŌĆÖt tried and tested.ŌĆØ┬Ā

Eric agrees. ŌĆ£There arenŌĆÖt a lot of opportunities for students to see adults in positions of authority or that they respect or admire model failure,ŌĆØ he says.╠²

Teachers can model risk-taking and ŌĆ£failureŌĆØ outside of what theyŌĆÖre teachingŌĆöby just being who they are. ŌĆ£I cycle and I have scars everywhere. The image in my head is ŌĆśIŌĆÖm a cyclist,ŌĆÖ not ŌĆśIŌĆÖm banged up,ŌĆÖŌĆØ she says. ŌĆ£They give me character and I keep riding.ŌĆØ┬Ā

Listen to the whole podcast episode here┬Āand subscribe to Science Connections: The Podcast here.╠²

About ├©▀õAVŌĆÖs Science Connections: The Podcast

Science is changing before our eyes, now more than ever. So how do we help kids figure that out? How are we preparing students to be the next generation of 21st-century scientists?

Join host Eric Cross as he sits down with educators, scientists, and knowledge experts to discuss how we can best support students in science classrooms. Listen to hear how you can inspire kids across the country to love learning science, and bring that magic into your classroom for your students.